Gaslamp's History

Though the Gaslamp Quarter Association was officially chartered in 1982 by the City of San Diego under State Law, the Gaslamp Quarter’s Merchant Association goes back several decades and the historic commercial district that would become the Gaslamp Quarter began as William Heath Davis’ New Town in 1850. The Gaslamp Quarter’s colorful history, combined with its modern-day, world-class boutiques, galleries, and restaurants, is what makes this urban district unlike any other.

1800s

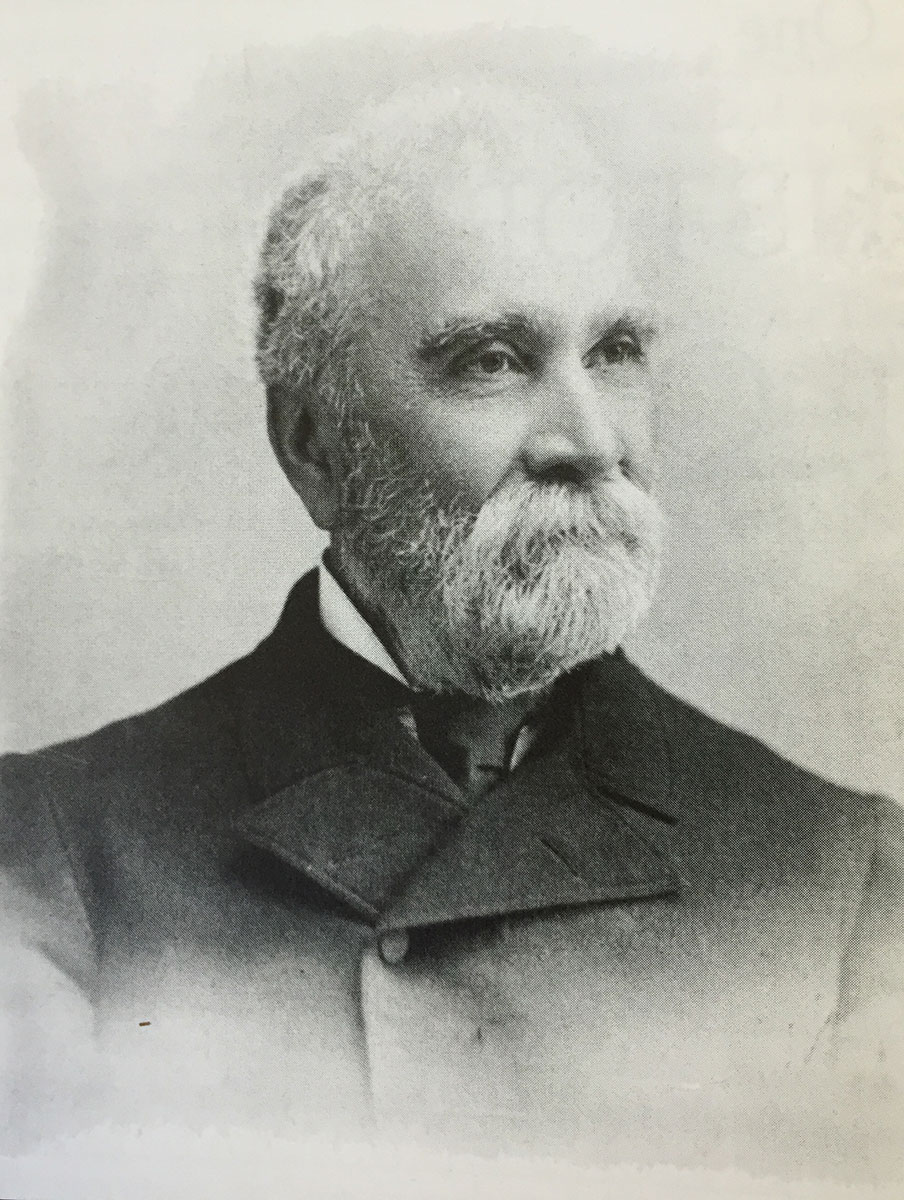

William Heath Davis.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

1850

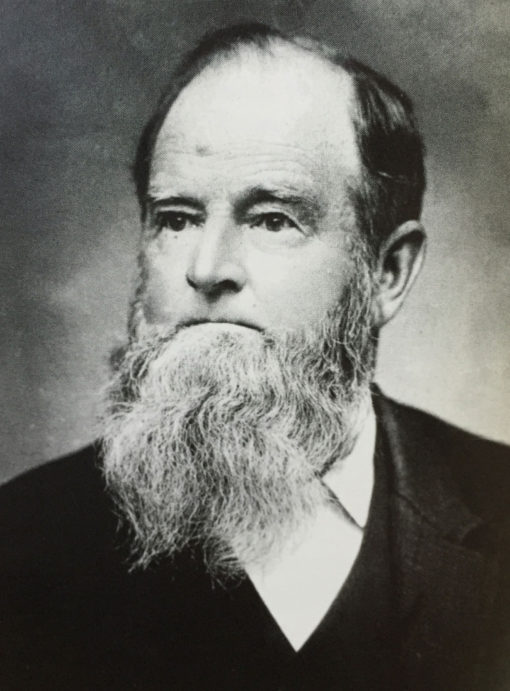

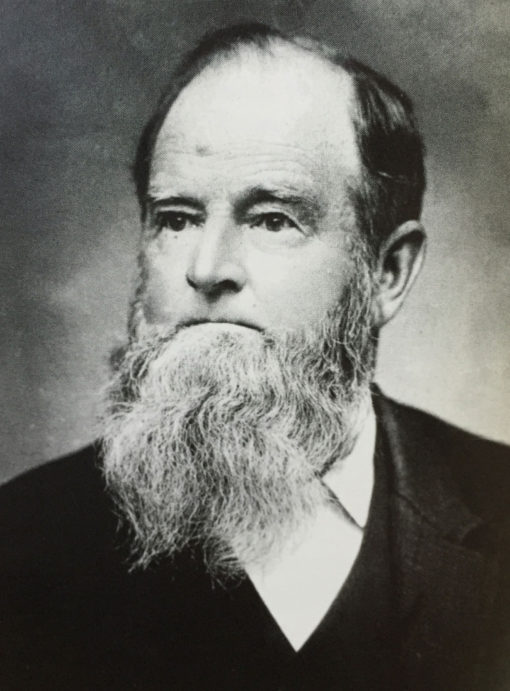

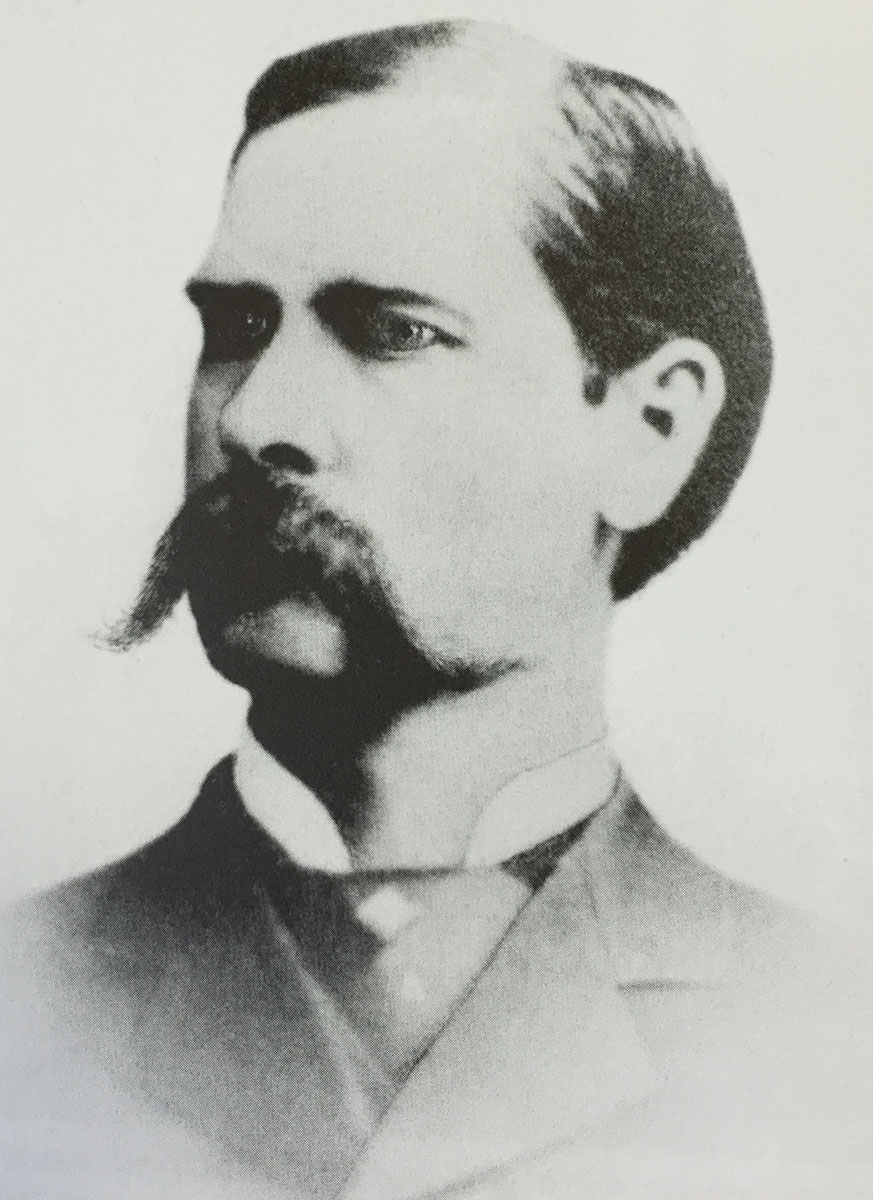

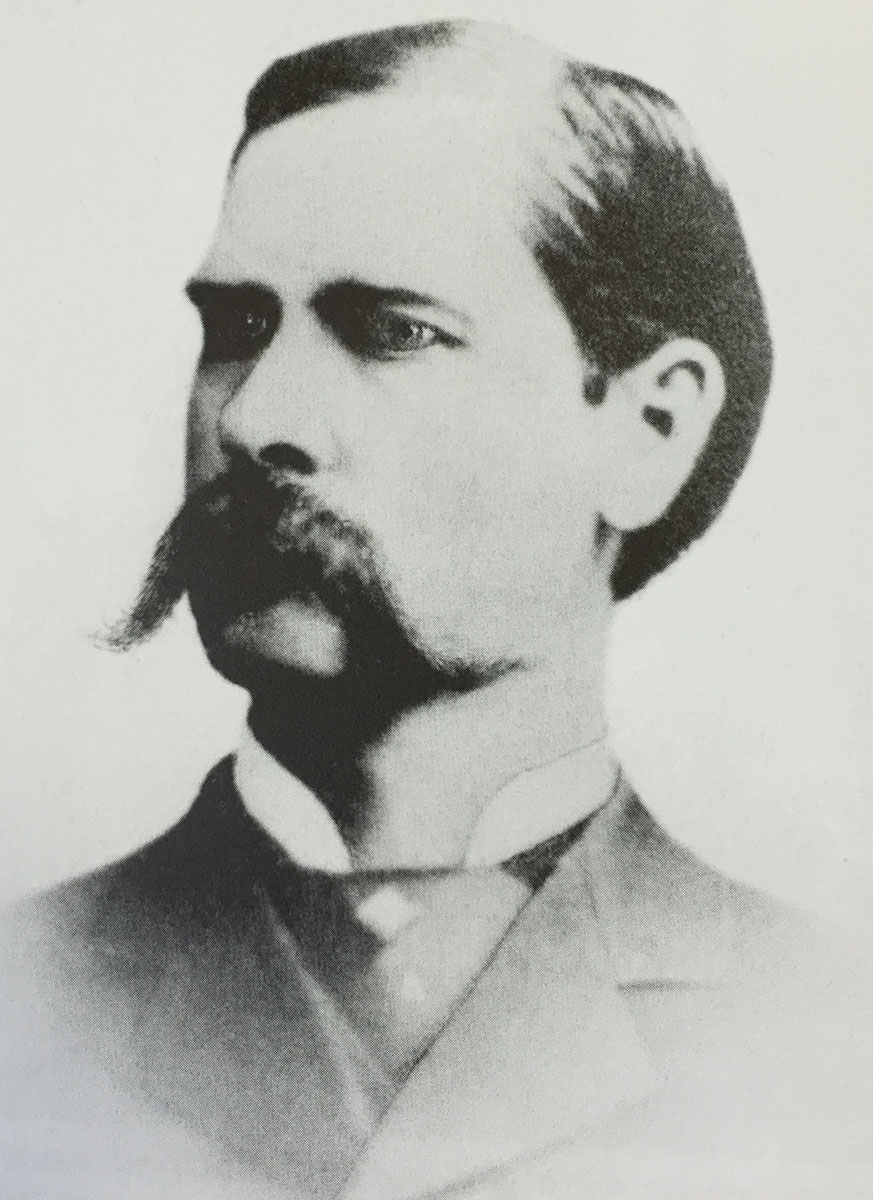

Alonzo Horton.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

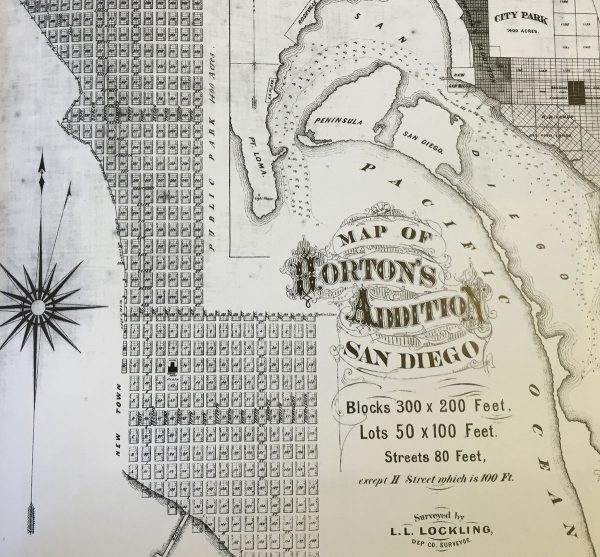

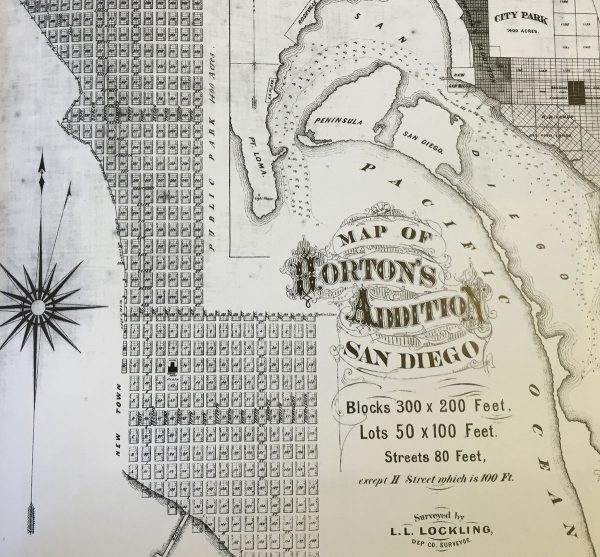

Map of Horton’s Addition.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

Above: Alonzo Horton. Below: Map of Horton’s Addition.

Photo Credits: San Diego Historical Society

1867

1869

Late 1800s Parade on Fifth Avenue.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

1870

Wyatt Earp.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

View from 5th and Island in 1887.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

Above: Wyatt Earp. Below: View from 5th and Island in 1887.

Photo Credits: San Diego Historical Society

1880s

1885

1887

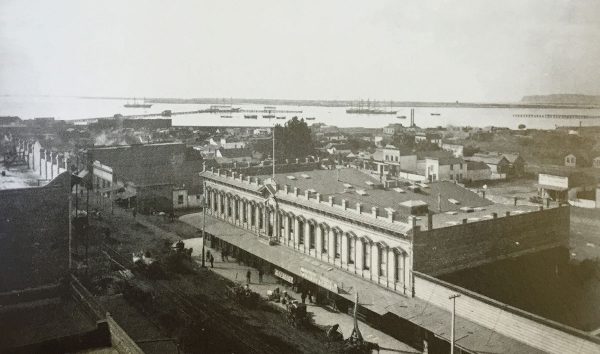

View of Backesto Building and San Diego Bay.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

1888

1894

1900s

1903

1909

The Stingaree Raid of 1912.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

1912

1913

Ah Quin.

Photo Credit: San Diego Historical Society

1914

1920

Post WWII

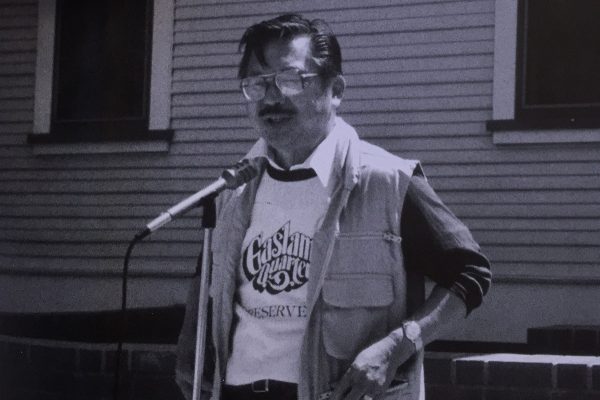

City Councilmember Tom Hom, Early 1970s.

Photo Credit: Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation

1974

1976

1980

1982

1986

1988

Installing the Gaslamp Quarter Archway.

Photo Credit: Roy Flahive

1990

Gaslamp Quarter Archway in 1990.

Photo Credit: Roy Flahive

1991

2000s

2012 Gaslamp Quarter Archway Rehabilitation.

Photo Credit: Byron Wade

Gaslamp Quarter Archway, post-refurbishment in 2013.

Photo Credit: Gaslamp Quarter Association

Above: 2012 Gaslamp Quarter Archway Rehabilitation.

Photo Credit: Byron Wade.

Below: Gaslamp Quarter Archway, post-refurbishment in 2013.

Photo Credit: Gaslamp Quarter Association

2012-2013

Today

Still Curious?

For more information on the history of the Gaslamp Quarter, visit the Gaslamp Museum at 410 Island Avenue or the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation’s website at http://www.gaslampfoundation.org.